OpenAI’s hype machine faces a corporate challenge

By Karen Kwok

If there’s one thing Sam Altman knows, it’s how to grab attention. The boss of ChatGPT developer OpenAI can be seen on viral clips in which his likeness, generated by the company’s buzzy new Sora video model, steals computer chips. He regularly makes waves with announcements on X, which is owned by his arch-rival Elon Musk. He’s even unveiled grand investment plans at the White House. He’s good at keeping attention, too, with the company boasting 800 million weekly active users and a billion on the horizon. The real test for Altman and his competitors, though, is how well they can win over a more skeptical audience: big corporations.

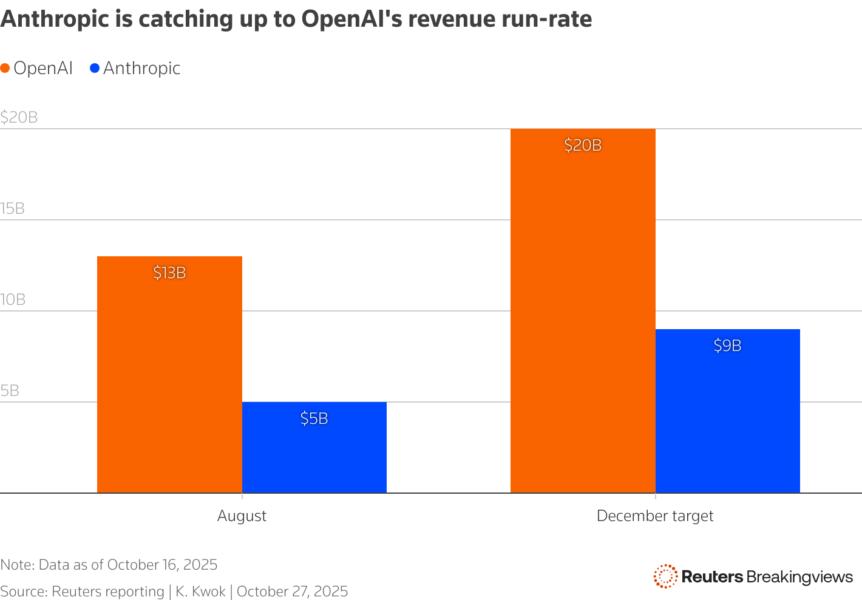

Right now, OpenAI makes most of its money from regular people. The company’s annualized rate of revenue has reached $13 billion, and may hit $20 billion by the end of this year. About 70% of that comes from consumers paying for ChatGPT subscriptions. Over 5% of the chatbot’s users pay, though that’s just enough to cover the immediate cost of the computing power generating responses for everyone, if not OpenAI’s other enormous expenses.

The remaining 30% of revenue comes from enterprise offerings. Some of that is via usage-based pricing for accessing OpenAI’s large language models directly through what is known as an application programming interface (API). Customers are billed per unit of input or output, known as a token. Prices for these tokens start high when a cutting-edge model is new, but quickly go into free-fall: between GPT-4’s initial release and the refined GPT-4o Mini model released 18 months later, costs fell by 99%.

It’s therefore a constant war of attrition to keep big companies hooked on the latest and greatest — and most expensive — models. One way to get a little more stability, though, is to sign enterprise clients like Morgan Stanley MS and T-Mobile

TMUS up to bigger, more comprehensive contracts. After all, they can be willing to do so when OpenAI can demonstrate a clear return on investment, say by helping a call center resolve tickets more quickly, or by speeding up programmers’ code reviews.

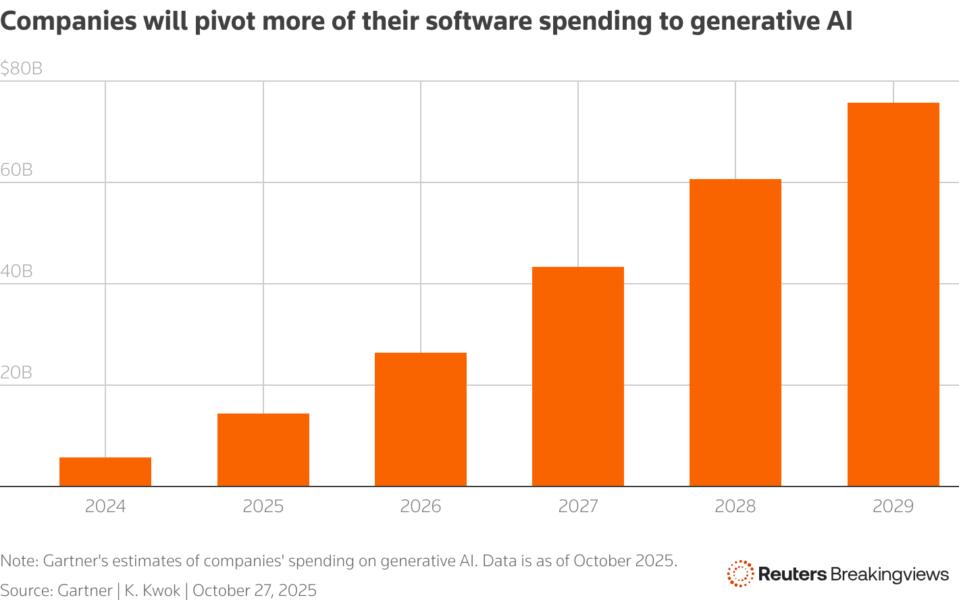

If they can be convinced, corporations are a gigantic prize to play for. Gartner IT forecasts that enterprise software spending will reach $2 trillion globally by 2029, of which a mere $76 billion will go to generative AI. If chatbots really are as disruptive as their boosters suggest, they could snare far more of that budget.

To boot, consumers are fickle, switching constantly between new and shiny products. Look, for instance, at Alphabet-developed Gemini GOOG, which has doubled market share to 14% over the last year as ChatGPT’s share has slipped, according to Similarweb data. Corporate buyers can be much stickier. Once a system is integrated and covered by a multimillion-dollar contract, switching becomes a hassle, making every enterprise deal more lucrative over time.

Consumer ubiquity can help pry open enterprise wallets. Engineers discovering ChatGPT through personal use may push for adoption of the familiar tool inside their organizations. When companies eventually sign up, they pay for added security, compliance features, and administrative functions, often at much higher price points.

That cost — and the dependence on OpenAI’s computing resources, which Altman frequently points out are overstretched — can become a sticking point, though. Cohere, a $7 billion Nvidia-backed NVDA Canadian AI lab focusing on the enterprise, takes a different tack. Unlike OpenAI, Cohere doesn’t handle client data. Instead, a customer sets up their own secure servers, powered by their own stash of rented or owned chips, and runs the company’s models themselves. This model offers a security advantage for regulated industries like healthcare, finance, and government, while also helping Cohere sidestep the enormous cost of actually running its models. As a result, it boasts a software-like gross profit margin above 60%, according to one source familiar with the matter, and is targeting profitability by 2029. OpenAI’s gross margin is closer to 40%.

Altman’s greatest rival in this domain, though, may be fellow AI lab Anthropic, backed by Amazon.com

Claude’s impressive coding performance is turbocharging its growth. Reuters reports that Anthropic expects to triple its annualized revenue run-rate to $26 billion next year. OpenAI is still edging ahead on some measures. According to financial platform Ramp, as of September, 36% of U.S. companies with paid subscriptions to AI models, platforms and tools choose the ChatGPT maker, versus Anthropic’s 12%. Yet Menlo Ventures, which backs Amodei’s firm, gives it the edge in market share for coding, specifically, which seems to be reflected in the popularity of models chosen by users of programming platform Cursor. Anthropic is also catching up on revenue, targeting a $9 billion annualized rate by 2025’s end, Reuters has reported, versus the $20 billion forecast by OpenAI.

Meanwhile, open-source players are also eating into the pie. France’s Mistral, recently valued at $13 billion following an investment from chip technology developer ASML ASML, lets customers train models in-house. And in a twist, some Western tech companies — including Airbnb

ABNB — are turning to Chinese models like Qwen, built by Alibaba

BABA, for their affordability and flexibility. Qwen’s market share on API access tool OpenRouter has reached 7%, barely below OpenAI. Brian Chesky, boss of travel platform Airbnb, said his company relies heavily on the model.

Sam Altman may be the king of the consumer for now, as novelties like Sora or new ChatGPT updates catch fire online. Winning over corporate bean-counters is a less thrilling, though no less urgent, slog.

Follow Karen Kwok on LinkedIn and X.